When you think of Japanese tattoos—known as Irezumi—you might picture full-body suits of mythical dragons, koi fish swimming through waves, or fierce oni glaring from a backpiece. But beneath those bold designs lies a story woven with beauty, rebellion, artistry, and, well... a bit of criminal flair.

Let’s take a deep dive into the fascinating and ink-soaked journey of Irezumi, where skin tells tales of samurai, outlaws, and underground honor codes. Buckle up—it’s about to get colorful.

What Is Irezumi?

More Than Just "Japanese Tattoos"

“Irezumi” (入れ墨 or 彫り物) literally translates to “inserting ink” or “tattooing” in Japanese. But Irezumi isn’t just a generic term for tattoo—it refers specifically to traditional Japanese tattooing, known for its large-scale, vivid, and deeply symbolic body art.

From shoulder-to-thigh bodysuits to intricate chest panels and arm sleeves, Irezumi is about storytelling, not trend-following. And unlike your cousin's impulsive infinity symbol, Irezumi pieces are often planned over years and involve intense pain, devotion, and respect for cultural lineage.

Hand-Poked vs. Machine

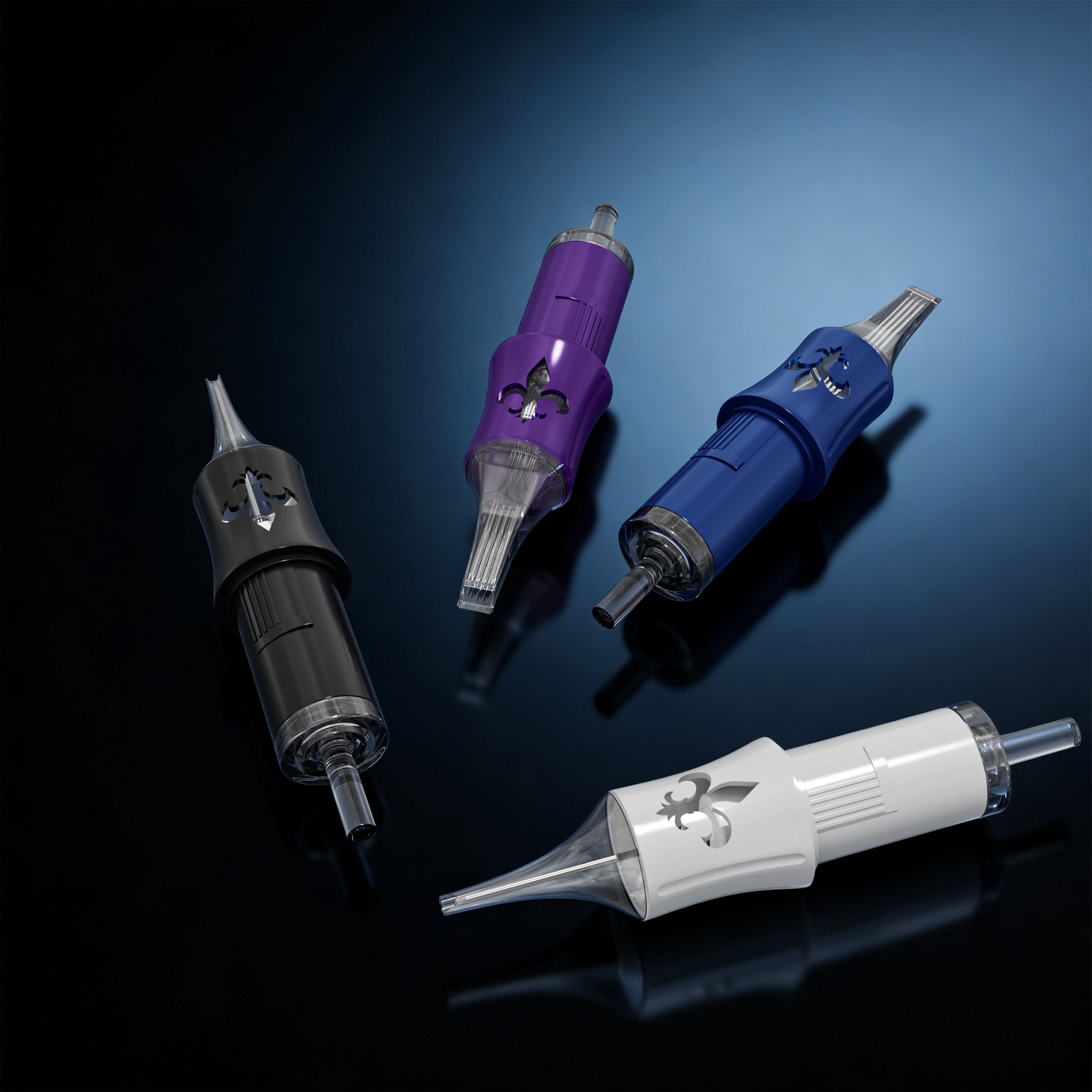

True Irezumi is traditionally done by tebori, a manual technique where artists hand-poke pigment into the skin using a set of needles attached to a wooden stick. Yes—this is the slow, steady ninja-style method of tattooing. Today, many modern Japanese artists also use tattoo machines, blending old and new techniques while still preserving the soul of the style.

Ancient Beginnings: Tattoos in Japan Before the Crime Drama

From Spiritual Marks to Tribal Status

Believe it or not, tattoos in Japan didn’t start out as taboo. The earliest evidence dates back to the Jōmon period (around 10,000 BCE to 300 BCE), when archaeologists believe clay figurines showed markings that may have symbolized spiritual or tribal meaning.

Later, during the Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE), Chinese historians wrote that some Japanese people tattooed their faces and bodies for decoration and status. These markings were seen as signs of beauty and power, not rebellion.

Tattoos as Punishment? Oh Yes, That Happened.

Fast forward to the Kofun period (300–600 CE), and tattoos took a darker turn. Around this time, tattoos shifted from symbols of status to marks of shame. Criminals were tattooed with symbols or words on their faces, arms, or foreheads to mark them for life. It was basically an ancient, inked version of a criminal record you could never erase.

Different regions even had specific criminal tattoos. One might get a straight line on the arm for theft, another might get a character carved into their forehead. The more crimes you committed, the more your body turned into a walking billboard for bad decisions.

Edo Period: Crime, Art, and the Birth of Irezumi Culture

Outlaws, Firemen, and Floating World Rebels

Ah, the Edo period (1603–1868). Japan was isolated from the world, samurai ruled, and woodblock art was booming. This era saw the true birth of decorative Irezumi as we know it—full of color, folklore, and rebellion.

Here’s the twist: because tattooing was linked to criminals, outlaws began to reclaim ink as their own form of power. They embraced full-body tattoos as a form of honor, identity, and resistance. Imagine saying, “You think I’m a criminal? Cool. Let me give you a reason to stare.”

And it wasn’t just criminals. Edo firemen, known as hikeshi, also rocked tattoos. These guys risked their lives battling wooden building fires (which happened a lot), and their tattoos—dragons, tigers, gods—were worn like spiritual armor. They were the original tattooed badasses.

Ukiyo-e and Tattoo Design

During this time, ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) exploded in popularity. Artists like Kuniyoshi began illustrating famous Chinese outlaw tales, especially the “Suikoden” (Water Margin) saga. These prints showed tattooed heroes battling injustice—think ancient anime with body ink.

Tattoo artists (many of whom were woodblock carvers themselves) took direct inspiration from these prints, turning the characters’ mythical tattoos into real-life Irezumi pieces. Full back tattoos featuring fierce warriors, tigers, and water dragons became symbols of strength and loyalty.

Meiji Period Crackdown: Tattoos Go Underground

Western Embarrassment and Banning the Ink

By the late 1800s, Japan started opening up to the West during the Meiji Restoration. The government, eager to impress foreign powers, suddenly decided tattoos looked barbaric and uncivilized. So, in 1872, they banned tattooing entirely.

Yes, really.

Ironically, while tattoos were outlawed at home, Western sailors and tourists came to Japan specifically to get traditional Irezumi—turning artists into quiet underground legends. It’s like your favorite punk band getting banned but then doing secret basement shows for die-hard fans.

The Yakuza Connection Begins

With tattooing pushed underground, the Yakuza (Japanese organized crime syndicates) began adopting Irezumi as a badge of honor. Full-body tattoos were used to signify allegiance, toughness, and loyalty. And because the process was painful, expensive, and illegal, it became a powerful initiation ritual.

Tattoo shops operated in secrecy. Tattooed men hid their ink beneath suits and avoided public baths. But within their circles, the ink was a silent declaration: “I belong to something bigger—and I can take pain.”

This connection to the criminal world would define the public perception of Irezumi for decades to come.

Modern Times: Between Respect and Rebellion

Tattooing Becomes Legal Again (Sort Of)

Tattooing was technically legalized after WWII under the U.S. occupation. But let’s not pretend everything suddenly turned rosy. For much of the 20th century, tattoos in Japan remained controversial—especially in public spaces.

Even today, many Japanese onsens (hot springs), gyms, and pools ban tattooed individuals. The association with crime still lingers, even as attitudes begin to shift.

The Art of Irezumi Lives On

Despite the stigma, a new generation of tattoo artists and collectors are preserving and evolving Irezumi. Some still work by tebori, while others use modern tattoo machines to honor the tradition with contemporary twists.

Japanese tattooing is now recognized globally for its beauty and depth. International fans travel to Japan just to get inked by legendary artists—and some wait years on waiting lists. It’s no longer just underground rebellion; it’s internationally respected art.

Cultural Controversies: Respecting Irezumi in a Global Tattoo World

Cultural Appropriation vs. Cultural Appreciation

Let’s talk real for a second. Japanese tattoos are admired around the world, but that doesn’t mean you can just slap a hannya mask on your bicep without understanding what it means.

Irezumi is sacred to many, and designs often have deep cultural or religious symbolism. If you’re going to wear Japanese-style tattoos, learn their meanings, honor their origins, and—please—we beg you—don’t get a “samurai koi dragon warrior” sleeve from a $99 walk-in shop in Las Vegas.

Japan’s Own Tattoo Identity Crisis

Interestingly, younger generations in Japan are starting to embrace tattoos again—but carefully. While some see them as fashionable, many still hide them due to family or work-related shame. It’s a strange dance between modern style and cultural caution.

And yet, the ink spreads. Quietly, powerfully, beautifully.

Irezumi Icons: Symbols That Speak Volumes

The Koi Fish

Swimming upstream against waterfalls, the koi represents perseverance and transformation. It’s said koi can become dragons, symbolizing personal growth and bravery.

Dragons

Not the fire-breathing Western kind—Japanese dragons are wise, protective, and elemental. Often wrapped around the body, they signify strength, wisdom, and balance.

Hannya Masks

These terrifying female demons symbolize jealousy, pain, and vengeance. But they also represent the duality of human emotion and the power of spiritual redemption.

Cherry Blossoms

Sakura, the cherry blossom, represents the fleeting nature of life. A common background motif, they remind us that beauty—and life—is short-lived and precious.

Final Thoughts: Inked with Legacy

The story of Irezumi is anything but boring. From tribal rituals to criminal punishments, from outlaw rebellion to underground art, Japanese tattoos have survived centuries of stigma to emerge as one of the most revered tattoo styles in the world.

To wear Irezumi is to wear a piece of Japanese history, a symbol of resilience, identity, and art passed down through the skin. It’s not just ink—it’s a statement. One that says: “I know where this comes from. And I respect the story.”

So whether you’re an ink-lover, tattoo historian, or just someone who stumbled down a rabbit hole of dragon backpieces, remember this: behind every Irezumi tattoo lies a tale worth telling.

And it’s probably cooler than your cousin’s infinity symbol.

Share:

The Ancient Roots and Modern Expressions of Tattoo Culture

Ancient Tattoos: What Mummies Can Teach Us About Ink